revisiting butoh

Marisa C. Hayes on Butoh Workshops at the Kazuo Ohno Dance Studio

Walking Towards Authenticity: Butoh Workshops at the Kazuo Ohno Dance Studio

Emotion must be ever present, full blooded emotion.

This finger here can provoke an emotional response.

- Kazuo Ohno

Throughout the 1960s Kazuo Ohno, alongside Tatsumi Hijikata, shattered conventions in the Japanese contemporary dance scene, then based largely on copying Western styles of modern dance. These two artists dared to confront the aftermath of the atomic bomb and embody moments of darkness and decay in post-war Japanese society. Their departure from traditional aesthetics and disillusionment with the country's rapid Westernisation shocked audiences and fell in direct opposition to the national effort undertaken to collectively rebuild and forget. Today Butoh has evolved into various subcategories and styles, and can be found in some form on almost every continent. Butoh's source, however, is still a common thread among most Butoh dancers who trace their lineage either directly or indirectly to Hijikata or Ohno.

Nestled atop a hill in Yokohama's quiet suburb of Kamihoshikawa, Kazuo Ohno and his son Yoshito open their home studio three times a week to any individual interested in studying Butoh. Drop-in visitors are welcome, and while a small handful of local regulars attend class faithfully, most are foreigners who make the journey in honour of Butoh's co-founder. At 103 years of age, Ohno is currently in poor health and hasn't officially taught for a decade (until recently, he continued to make regular appearances at the studio), but his workshops have continued, led by Yoshito Ohno, an accomplished dancer and teacher, celebrated for his childhood appearance in Kinjiki, the first Butoh performance, directed by Hijikata in 1959.

Like his father, Yoshito is committed to sharing the art of Butoh without regard to cultural background, age, gender or ability. The Ohnos underline Butoh's universal principles in lieu of the cultural uniqueness embraced by a few Japanese artists who argue that Japanese body types, particularly the common bowlegged quality of the legs known as o-kyaku, and Butoh's origins in the aftermath of World War II, make this art form inaccessible to non-Japanese students. Despite the Ohnos' willingness to share Butoh with a wide-ranging array of pupils, the training itself features strong links with Japanese culture and theatre, lending the dance and its study an undeniable specificity.

The first and most essential element of Butoh training taught at the Ohno studio (and in many Butoh workshops) is Zero Walking. The Zen concept of emptiness, often represented in Japanese aesthetics by the colour white or an empty ring, is at the heart of this fundamental movement. Zero Walking is similar to Zen walking meditations: participants are asked to take their time as they cross the studio, erect but relaxed, feeling every bodily sensation as the feet slowly progress towards the other side of the room. Long-time students often take 30 minutes or more to traverse the floor of the Ohnos' 99-square-metre studio. Through careful awareness and attention to breath, this walking encourages the body to become a clean slate. Yoshito speaks of the body as a vessel that must be emptied before it can take form through dance. The embodiment comes in response to stimuli originating from a variety of sources, such as visual imagery, sound and poetry. After a good deal of practice with this deceptively simple walk, one uses it as a starting point, both mentally (a state of nothingness to be transformed through response) and physically (an upright central axis which can then be contorted and embellished).

Despite visible traces of German expressionism's influence, and a departure from the codified movements of classic Japanese theatre, Butoh nonetheless owes several of its defining features to the traditional performing arts native to Japan. Many Butoh dancers, Kazuo Ohno among them, utilise movements characterised by an undulating slowness inspired by Noh theatre, known for its reserved and drawn-out choreography. The slowness doesn't translate to reserve in Butoh (in this sense, the commotion of Kabuki theatre is often shared), but the idea of embodiment in Noh, of simply being without moving, is fundamental and taught extensively at the Ohno studio. To illustrate this concept, Yoshito borrows an exercise used to train Noh performers. He places a feathery sheet of rice paper between the legs of each student. The paper feels weightless, like silk, and its presence can scarcely be felt. He asks students to cross the studio without allowing the paper to fall or move from its position. The legs must be held together so tightly in order to protect the paper from slipping that participants can do little more than tread delicately. As Kazuo Ohno notes in his Workshop Words, 'inaction, more than physical movement, affects us on a much deeper level'.

In addition to appreciating stillness, abandoning habit is another vital concept outlined during Yoshito's courses. He asks students to improvise, not to imagine what will come next or where the body in space will move, but rather to feel each moment deeply so that one flows intuitively into the next. Easier said than done, Yoshito's friendly reminders come in the form of both verbal and physical interruptions. Once, when given a soccer ball to dance with, I cradled it in my upturned palm. Yoshito approached and knocked it out of my hand. Instinctively, my reflexes responded and caught the ball before it could fall to the ground. He gently mouthed 'no', placed the ball back in my palm and hit it to the floor once more. My eyes followed the ball as it rolled away and out of reach. Through these interventions, students are forced to follow another path in their dancing, free from attachment or preconceived notions of what a dance will resemble compositionally or symbolically. Kazuo Ohno's commitment to open-ended possibility is delightfully noted in Sandra Horton Fraleigh's Dancing into Darkness. While holding a postal letter in his hands, Kazuo said to a group of students: 'Do not think what shall I do? Move randomly out of intuition. I do not need to look inside this letter to see what is there. If I have perfect freedom I can do anything with it. Instead of reading the letter, I can eat it.' He then proceeded to bite into the envelope. During another exercise in which each student receives a flower, Yoshito asks participants to show their love for the flowers through their dancing. In my experience, the majority of the class delicately holds onto each individual flower, as if clutching a new-born baby. Yoshito, however, once suggested dropping them to the floor and stepping on them, while continuing to express love. This is not a masochistic approach, but rather an effort to free the body and mind of conventions regarding how one expresses an idea and enacts it physically.

In order to maintain this dedication to movement's wide potential, the Ohnos employ full use of the body. Hands, mouth, and facial features, often ignored in Western dance traditions, are all important fodder for exploration in Butoh. Seeing is treated with particular care, as Yoshito constantly challenges his students to examine how the eyes and body interact. For the Ohnos, where the eyes are located and how they function is crucial and transcends literal notions of visual sight. Yoshito teaches that the entire body is a receptor of light, and that it is therefore capable of assimilating both its environment and its internal landscape. In one exercise he asks students to crawl on the floor, letting their hands act as eyes. This practice encourages an acute sense of focus that furthers a student's journey towards an authentic means of expression.

Whether it be in response to music (Kazuo loves the Japanese shamisen as much as he adores Elvis Presley), a visual cue (Yoshito once held up a photo of dead child in Iraq and simply said 'move'), a verbal directive ('become the sun') or an external prop (the flower), Butoh demands an immediate act of embodiment from its dancers. Kazuo's most famous quote, 'no thinking, only soul', sums up the emotional commitment required - one that quickly falls into the realm of farce if not approached with the utmost degree of sincerity. At the Kazuo Ohno Dance Studio, students receive concentrated training, sometimes focusing on a single exercise for the entire two-hour class. The ultimate goal, as Kazuo has outlined, is to 'imbue every single instant with the heart beat of your soul'.

— Marisa C. Hayes

. . .

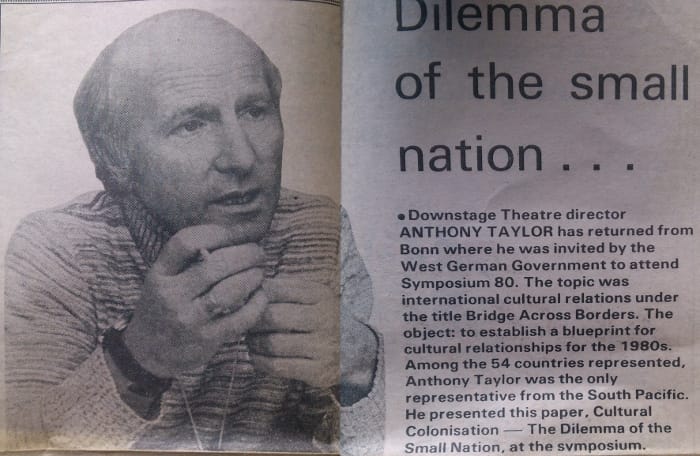

looking for an image, perhaps of Hijikata Tatsumi, perhaps in Heliogabalus, I came across this http://www.mattin.org/recordings/heliogabalus.html, the second item refers to the kiwi underground ... Mattin, we read, is an artist, musician and theorist working conceptually with noise and improvisation. Through his practice, writing and pedagogy, he explores performative forms of estrangement as a way to deal with structural alienation.