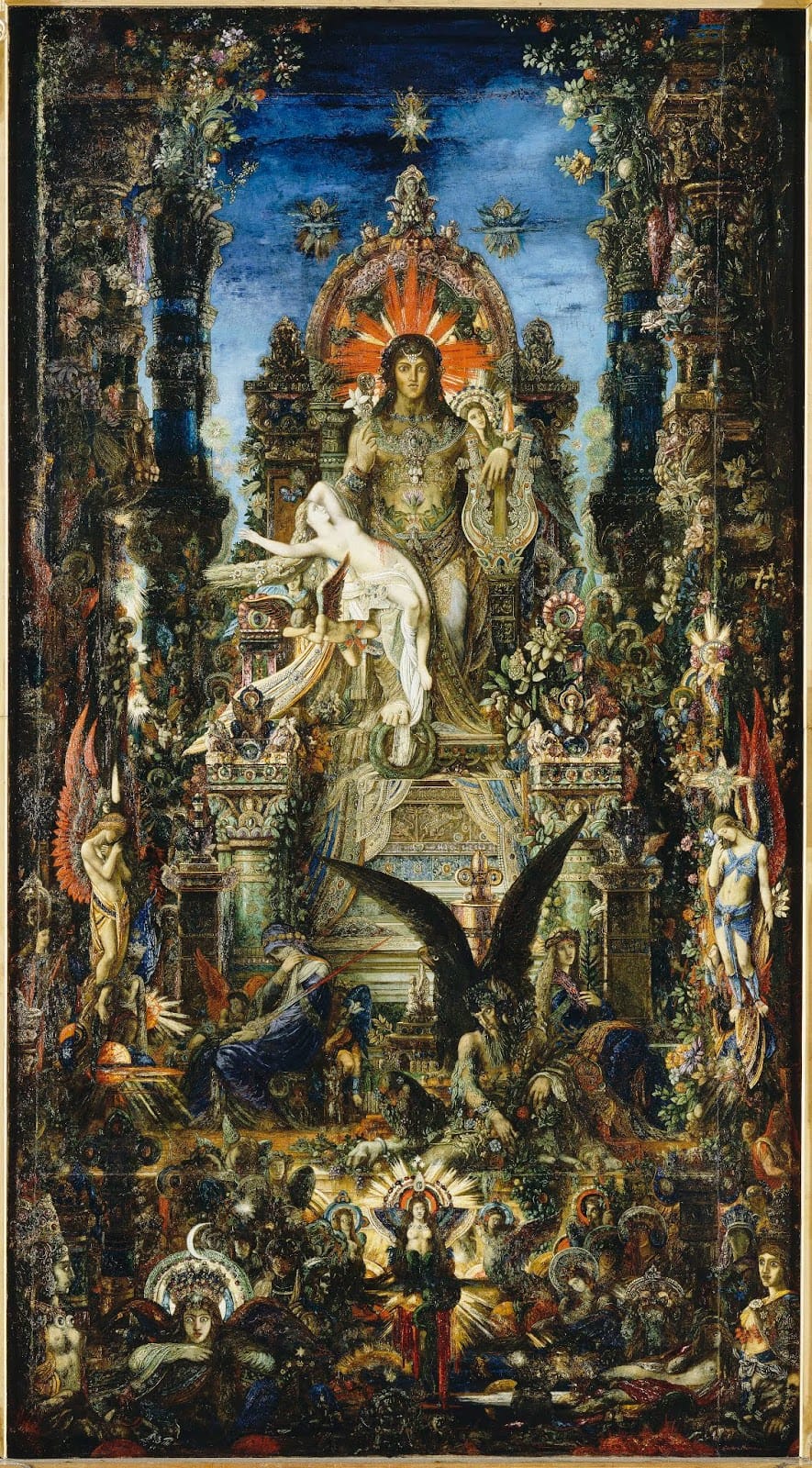

Semele I, II

the work on Semele was preparatory for a project submitted to and denied by CNZ for funding in 2009. It was called Love Project and comprised 4 interwoven stage-works at 4 different venues and in different styles. Go to the LP9 at the bottom of this post if you would like to know more.

Semele I

Semele in Olympus, by way of an Introduction to The Love Project, a modular drama for indeterminate forces, taking “as long as possible”

Even to the height of mighty Olympus (or Όλυμπος), reports of the exceptional beauty of the child had reached. The king of all the gods, who has his throne upon that mountain, Zeus (or Ζεύς), heard them. He watched and waited.The child’s mother, Harmonia (or Αρμονία), was born of the unlikely union between love and war, Aphrodite (or Ἀφροδίτη) and Ares (or Ἄρης), making her uncles, on her mother’s side, fear and panic, Deimos (or Δεῖμος) and Phobos ( or Φόβος). Her father, the hero Cadmus (or Κάδμος), was founder of the city of Thebes; he’d brought his immortal bride, Harmonia, to the city, where she’d given him three daughters, Ino, Agave, Autonoë, and a son, Polydoros, before the fourth daughter, whom it pleased Zeus to look on from afar, who was called Semele (or Σεμέλη).

The child flourished in the well-appointed city of Thebes, a city happy to have as wise and just a sovereign as Semele’s father, Cadmus. Her mother bestowed on her an harmonious disposition, to add to the almost-divine radiance of her limbs and features, a beauty of mind or soul, and balance in all her inward and outward attributes and virtues. So she grew to womanhood; to an immortal eye, this happened in an instant.

When she was ready enough, Zeus one night alighted on the flat roof of the palace. He swung himself down into her bedchamber, silencing the young woman’s nurse, Beroe, who still slept in her room, with a whiff of sevoflurane, a drug the god had stolen from his wife, Hera; since Hera kept a veritable pharmacy of ethers and barbiturates, haloalkanes and opioids.

From the awesome majesty of his divine body, Zeus changed to mortal form, wherein he was yet a paragon of physical strength and male beauty. Approaching her bed and for the first time within arm’s reach of Semele, Zeus comprehended the distance by which her pulchritude outstripped her years and knew that it was this gift of the gods, even as an infant swaddled in the lap of her nurse, Beroe, had drawn his attention to her.

But Semele was born mortal and for her Zeus had prepared and brought with him a draft made from pieces of the heart of Zagreus, his son, whom he had off his daughter, Persephone, when he went to her and lay with her in the shape of a serpent. His son’s heart had been all that was left to Zeus after the Titans, acting on the orders of his wife, Hera, found Zagreus in the care of the dancing Curetes (or Κορύβαντες) and pulled him to bits and devoured him, half raw, half cooked.

Zeus had had a son to rule Olympus after him, had lost him to Hera’s jealousy, and had contrived a plan to bring him back. He would feed Semele the pieces of the heart, which, when incorporated into her body, although she was human and would be a mortal mother, would mingle with Zeus’s seed when he impregnated her, to give forth a god. Semele, the ruler of all the gods thus reasoned, would bear him his son, named Zagreus, anew.

Semele woke up to utter darkness and felt not seeing the presence of the god in her room, before she heard him. Artemis (or Ἄρτεμις), the eternal virgin, another of Zeus’s daughters, over whom he had exercised his influence, had in turn used hers, so that she need not bear witness to her father sleeping with the mortal, Semele, to steal the moon’s light away, while she hunted in other quarters.

Zeus then spoke to Semele and she immediately knew him, for his voice was deep and rolled like thunder, pressing her down onto the bed, making her whole body quake. He told her to drink the draft and standing beside her bed even brought it to her lips and held her shoulders so that the warmth of the heart of Zagreus going down her throat into her belly was nothing compared to that passing through his arm and from the nearness of his chest to her: she felt his breath on her face and smelt in it the charge in the air that precedes a summer storm.

Semele emptied the cup down to the final drop without a thought as to what it might have been, too distracted was she, excited by the bedside manner of the king of all the gods. But as soon as she was finished, Zeus lay down with her on the bed and saying not one word further, he had intercourse with her.

The next morning, Semele was ashamed: even if it was a god, even if it was that god, how could she prove it? and, what had she done? She prevailed on her nurse, Beroe, who had awoken none the wiser, to burn her sheets and to destroy any evidence she might find of a man having been there.

In this way, neither her father, Cadmus, nor mother, Harmonia, found out a thing. The very absence of the moon, on that occasion and on all subsequent visits by the god, they rationalised away and thought no more of than it were a season of cloudy nights and stormy presages, which never seemed to amount to the promised thunderstorm and did not achieve that relief, which is availed when the weather finally breaks.

For Semele, also, the nightly visits brought no relief: through the days she couldn’t wait for her lover’s touch and by night all she yearned for besides his touch was the light to see him by, to look into his eyes, and the sound of his voice, because he never again spoke to her as he did the first time, asking her to drink the heart-seeds of his son.

Semele gradually lost confidence that the god loved her, because he gave her none that he did; and without his reassurance, she began to suppose that he might, in fact, despise her: to all her requests to look on him, to hear him speak a single word, whether of love or despite, he remained dumb. He made love to her silently and, as she had from the first taken care that their love-making stayed secret, secretly.

The darkness, the silence and the secrecy took their toll on Semele. That she had fallen pregnant and that her efforts at secrecy could no longer claim to be rewarded, the secret being out, did not at all lessen or mitigate but rather increased the weight and strain under which the god’s love placed her. Hera, meanwhile, on high Olympus, heard and soon saw for herself, in Semele’s burgeoning belly, the extent of her husband’s betrayal.

One morning, disguised as Beroe, her nurse, Hera appeared to Semele and while the latter wept with frustration at being so used by the god, Zeus, she told her exactly what she wanted to hear. She consoled her by encouraging her indignation at her lover’s offhand treatment and persuading her she ought by rights to demand Zeus come to her, not like a thief, silently stealing in under cover of darkness, but in all the splendour and majesty with which he visited his wife.

“Ask Zeus to come to you as he comes to Hera, so you may know what pleasure it is to sleep with a god.”

To which end, Hera, as Beroe, gave Semele to know an oath even a god would not dare break, that by the river Styx (or Στυξ) Zeus should swear to grant whatever she asked of him.

The same night, rather than, as she was wont to do, asking for a light to see his eyes, a word to know his heart, Semele put aside all caution and presented her case: since Zeus had not answered her constant badgering or met any of her demands, she from henceforth promised never again to question his silence or the need for darkness, if he would, instead of granting all, fulfil but a single one of her desires.

Semele refused to let him near her till he spoke. Unwilling to force the issue with a mortal woman bearing his divine progeny, Zeus gave his assent. When they’d made love, Semele had him swear the oath by the river Styx and after he’d sworn it, she told him her one and only desire, which he was now bound to serve: that Zeus come to her in all his power and glory that she may know what pleasure it is to sleep with a god.

Regardful of the consequences, since for a god to lose his immortality is of greater consequence that for a mortal to lose her life, Zeus could not break his oath, could not resist Semele’s demand and did not prevaricate longer than the intervening day. Although he was reluctant, the following night he came to her as a god.

She lay bathed in moonlight waiting for him on her bed, until the refulgence of his awesome and immortal form cast that pale fire in the shade, and Semele felt the divine heat of Zeus, king of the gods.

The heat burnt Semele and the storm presaged in a season of cloudy nights broke with lightning and thunderbolts on her bed.

The splendour and majesty of Zeus consumed Semele and in love, by love was she immolated; and not silently, neither secretly, nor in darkness, as Semele burst out screaming and from her body came the immortal infant she’d carried for six long months.

Zeus wrested the baby from the flames, from the mother and from the thunder, and, slicing open his thigh in a long and deep wound, he placed it there, sewing the skin shut and enclosing it in this makeshift womb.

Three months later, the motherless child was born a second time; he was called Dionysus (or Διόνυσος), the twice-born, and the only god of the pantheon who, like Christ, dies.

This is not, however, the end of Semele’s story. Dionysus was given to Semele’s sister Ino and her husband, Althamus, to raise; and then, when Hera wreaked her terrible vengeance on these two foster parents as well, to the nymphs of Nysa.

Eventually, the child born by Semele and Zeus returned to Thebes; and, where “the chamber of Semele, still breathing sparks, was shaded by self-growing bunches of green leaves, which intoxicated the place with sweet odours,” Dionysus, the god, founded his rights.

As an adult, the divine Dionysus went looking for his mortal mother, Semele. He descended to Hades (or Ἅιδης) and retrieved her, and redeemed her, and himself, in the eyes of both Hera and of Zeus. Thus, in apotheosis, was Semele elevated to Olympus where she was made a goddess, Thyone; to whom Zeus addressed himself, saying,

“You have conceived a son who will make mortals forget their troubles.”

For in the mysteries of Dionysus are found the two linked and unequal intoxications, of duplicity, disguise and theatre, in which mortals, like the god himself, are born and die twice, and, of wine, in which they are said to forget, but, by this lesser truth, are led to remember a greater, which is freedom (or ελευθερία). The drunkenness of the latter leads inevitably to the former’s stage of all souls, of gods and men and fools; so mortals forgetting of their troubles may as well forget their mortality, and act out of, as much as in, character.

Thyone, then, the goddess, forever presides over the freedom of Dionysus (or Eleuthyrios), over the bacchanalia and mysteries, and over the Dionysian frenzies, which ensue as the rights of her son, the god.

Semele II

Semele is born beautiful. She is so beautiful, God falls in love with her.

The story goes that God visits Semele in mortal form. He drugs her nurse, who sleeps in the same room. It’s a big room, in the house of her father and mother, Cadmus and Harmonia. Beroe is sedated and God has no witnesses.

Beyond his obvious lust and desire to possess her, God has another purpose: he wants a son. He has watched Semele grow up. He has waited until she’s ready to bear a child. He has brought with him the chopped up pieces of his dead son’s heart.

His wife doesn’t understand him. She is a jealous woman. Barren, and not the mother, she had the Titans pull Zagreus to bits when he was still a child. All that remained of his half-cooked, half-eaten body was his heart.

God, along with his lust for Semele, is also a father in mourning. He convinces Semele to eat the pieces of Zagreus’s heart in a drink, so that his seed will mingle with the immortal remains of his dead son inside her; and, so that she will have an immortal child.

Semele falls in love with God on first hearing his voice. It would be love at first sight if it weren’t so dark and she will do anything for him. She eats the heart. They make love.

God telling her to drink the blood and eat the heart of Zagreus will be the last conversation she has with him. Every night for almost seven months, until she’s heavily pregnant, he will visit her and have sex with her, and stay silent.

God’s silence leads her to question his love for her. How can he love her and not speak? (Remember, she fell in love with his voice.) After being in love with God, she begins to doubt him.

The sex becomes mechanical. She talks all through it. God doesn’t say a thing.

She shouts at him, screams at him: nothing, no answer. Semele grows depressed and begins to resent and even to hate God.

It’s at this time that God’s wife learns of the affair. She sees that Semele is pregnant. Jealous, she disguises herself as Beroe, Semele’s old nurse, who is, again, drugged unconscious.

God’s wife plays on Semele’s insecurity. She tells her many is the time, down through the ages, that a man has tricked his way into a girl’s bed by using the name of God.

She says that she won’t know if he really is God or if he truly loves her until he comes to her in his immortal form, leaving behind his mortal one.

She asks her to imagine how good it must be for his wife when he comes to her bed as God himself. In her disguise as Beroe, she makes Semele jealous of her.

God’s wife shows Semele how to trick God into doing as she wishes, how to make him give his word and not go back on it. Semele puts the plan into action.

God gives his word to do as she asks. His voice affects her as it did before and she doesn’t follow through at once. But after they’ve made love, Semele asks him to come to her in his divine form when next he comes to her bed.

God protests that if he does it will kill her, because she is only mortal. What’s more, it will threaten the welfare of the baby she carries. Semele insists: if he loves her he must; if he cares for the child he must. She says she knows that he can’t go back on his word.

God comes to Semele as God. He grows bright enough to blind her; his increasing thunder deafens her; he gets hotter than the sun and burns her: he splits her womb wide open. The infant bursts from its burning mother.

God slits open his thigh and places the baby inside. Like a surrogate, he will bring it to full term here.

When it’s born, it will be called Dionysus, the twice-born, and, when grown, the mysteries will be performed in its name. These mysteries survive today in the various ecstatic rites of theatre and religion, sex, drugs, drunkenness and all the organised and social forms by which the senses are deranged.

Dionysus will bring his mother back from the dead. She will be made immortal by God and renamed Thyone.

As the immortal Thyone, she will preside over the religious and theatrical mysteries performed in the name of Dionysus. In turn, the mysteries performed will give her immortality.

LP9

the stories interweave through the four performances, in an art gallery, a theatre, a strip club, a karaoke bar:

1.

Semele and Zeus (or Jupiter): a classical myth with modern relevance – sex, sexual jealousy, surrogacy and cloning. A universal story.

Semele is so beautiful that the God falls in love with her. He visits her in human form and at the sound of his voice she in turn falls in love with him. The God’s wife grows jealous when she sees that Semele is pregnant. She convinces Semele to trick the God. She argues that Semele hasn’t loved him until she’s had him as a god, not as a man. The God has no choice. He comes to her in his immortal form and it burns Semele to death. The child, Dionysus, bursts from her womb. The God slits open his own body to bring it to full term there. When grown, Dionysus will rescue his mother from death and she will preside over those mysteries we call Dionysian and which include theatre.

2.

A summer party at a house in the country. Chekhov-style. What little action there is being character- and not plot-driven. The NZ landscape, in all its emptiness, is a character here. What is left unsaid motivates what happens. We learn of the undercurrents linking all four stories: destructive, passionate love, and belonging – the want of it, the lack of it.

A drift-work. Made from the residue of words, like a high-tide mark left by the preceding wash of language.

The action proceeds as if the characters from the NZ Chekhovian summer story have arrived on the shores of the story of Semele. They ask if they belong.

Like beach-combers, they pick through the washed up flotsam and jetsam. Their poetry lies in an attempt to make something of what’s left. Of what they find. As much as of what they bring.

A carcrash. Darkness presses against my face. Physical events. Through a succession of specific images a logic becomes apparent: it is the story of an ordinary life relived through a series of involuntary memories. A life literally flashes before our eyes. Dramatic images, political speeches, songs, shocks, pink rain. Memory and experience sit side by side. This is a poetry of sensations. We are neither at the end, nor at the beginning. Of a life. Perhaps we are in the middle.